We’ve all done it. Perhaps you didn’t want to attend an event, felt too lazy to do the dishes, or simply didn’t want to hurt someone’s feelings. Lying is undeniably human; animals, after all, don’t lie; a dog never tries to deceive you.

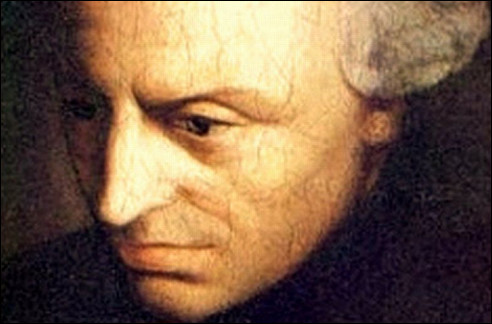

In one of his later essays, On the Supposed Right to Lie from Philanthropy, Immanuel Kant famously argues against the permissibility of lying. According to Kant, lying fundamentally contradicts his categorical imperative, which states: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”1 Lying is irrational because it is self-defeating. For Kant, lying fails this test because, if lying became a universal norm, trust would vanish entirely, and lies would lose all their advantage.

Benjamin Constant sharply criticized Kant’s strict imperative, which would make society impossible:

“The moral principle ‘it is a duty to tell the truth’ would, if taken unconditionally and singly, make any society impossible. We have proof of this in the very direct consequences drawn from this principle by a German philosopher, who goes so far as to maintain that it would be a crime to lie to a murderer who asked us whether a friend of ours whom he is pursuing has taken refuge in our house.”2

Constant argued that we have a duty to speak the truth, but only if it does not harm others. For Constant, truth-telling is indeed a duty, but only if it doesn’t harm others. Thus, lying to prevent harm, like protecting someone from a murderer, is permissible, even morally obligatory. Kant, however, disagrees vehemently. For him, lying always inflicts harm, either individually or to humanity at large. Therefore, people bear responsibility for any negative consequences resulting from their lies.

Critics have found Kant’s viewpoint extreme—some even absurd enough to suggest he suffered from Alzheimer’s.3 The idea that one should never lie, even to protect a friend from death, strikes many as morally troubling. Most of us instinctively understand that we would, in fact, lie to protect someone we care about. Failing to act (or to lie, in this case) might even seem like complicity in our friend’s harm.

Kant, however, stresses that we have very limited control over outcomes. We cannot accurately predict consequences. Kant’s infamous thought experiment is admittedly bizarre: meeting a murderer who calmly asks for your friend’s whereabouts, as if alerting authorities or dissuading him weren’t realistic alternatives. Therefore, Kant’s response is also quite bizarre. Kant insists that by lying, you contribute directly to whatever unforeseen consequences occur; and so, you bear responsibility. Conversely, by telling the truth, you supposedly allow the universe to unfold naturally, without personally manipulating outcomes.

But is Kant’s reasoning convincing? Even speaking the truth involves us in the chain of causation; we influence outcomes either way. It seems odd that Kant would claim moral responsibility only attaches to lying and not truth-telling.

For Kant, truthfulness underpins human rights because it respects others as autonomous beings, never as mere means. By lying, we deny autonomy to others, making us complicit in wrongdoing. Therefore, Kant emphatically concludes:

“To be truthful (honest) in all declarations is therefore a sacred command of reason prescribing unconditionally, one not to be restricted by any conveniences.”4

In other words, for Kant, lying is categorically unacceptable, even when the truth inconveniences us.

Kant focuses on virtuous conduct rather than unpredictable consequences. Consequentialist theories, like utilitarianism, stumble over precisely this difficulty: consequences are fundamentally unknowable. Kant maintains that while we can estimate possibilities, absolute certainty about outcomes remains impossible. Therefore, consequences shouldn’t influence our moral decisions.

This categorical stance even applies to seemingly harmless ‘white lies’, meant to spare someone’s feelings. Kant leaves room for ambiguity here: for example, should one tell a writer you enjoyed their poor work? Despite hints of leniency, Kant’s logic ultimately condemns all lies as irrational violations of the categorical imperative.

So what about cultural traditions like Santa Claus, or in Belgium, the similar tradition of Sinterklaas, which are based on a collective lie? Each year, Sinterklaas arrives in Antwerp with gifts for children, if they’ve behaved well. This collective fantasy brings joy and serves as a playful disciplinary tool (as Foucault might observe: behave, or no presents!). At first glance, there seems to be no negative consequences; everyone is happy.

Yet Kant would disrupt even this innocent tradition. We genuinely don’t know the full consequences of these harmless deceptions. Discovering that parents have lied could erode trust or permanently damage relationships. Perhaps children grow up believing lying about small things is acceptable, encouraging dishonesty in more significant matters. Or, worse still, what if children never discover the truth and live perpetually deceived? Believing in Santa Claus is cute when you’re five, but when you’re 35? Not so much.

Being critical, according to Kant, involves recognizing our limits. We continuously attempt to foresee consequences, but often must admit we simply don’t know. We cannot predict how someone will react to discovering they’ve been lied to. If the deception remains undiscovered, the person continues living inauthentically, based on falsehoods. Lying prevents genuine authenticity and obstructs true relationships.

Ultimately, for Kant, lying represents an attempt to reshape reality according to personal biases in an inauthentic and hubris-filled manner. Even seemingly trivial lies reveal arrogance, suggesting we falsely believe we can foresee outcomes. Lying misrepresents reality, deceives others, and undermines truthfulness, the cornerstone of trust and authenticity. Therefore, perhaps Kant’s stern stance might make sense after all: maybe it’s always better to tell the truth.

- Kant, Immanuel (1993) [1785]. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Translated by Ellington, James W. (3rd ed.). Hackett. p. 30. ↩︎

- Kant, Immanuel (1797), On the Supposed Right to Lie from Philanthropy. In Kant, Immanuel, Mary J. Gregor, and Allen William Wood. 1996. Practical Philosophy. The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant 1. Cambridge (U.K.): Cambridge university press. ↩︎

- Neiman, Susan. 2004. Evil in Modern Thought: An Alternative History of Philosophy; with a New Preface by the Author. 7. print., 1. paperback print. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press. ↩︎

- Kant, 1797, 613. ↩︎

Leave a comment