Why don’t we like our jobs?

Let me begin with a provocative claim: most people don’t really enjoy their jobs. Another claim, equally unsettling, is that many jobs are not only disliked but also pointless. At the same time, we live in a culture terrified of job loss—politicians like Barack Obama frequently warned of the dangers of jobs disappearing, and the media today echoes similar concerns about automation and artificial intelligence.

Yet, why should we fear the disappearance of something we do not even enjoy? To explore this paradox, I want to examine the concept of alienation from work, a theme introduced by Karl Marx and later expanded by Erich Fromm with a psychological dimension. Along the way, I’ll bring in David Graeber’s notion of “bullshit jobs,” which illustrates the absurdity of much contemporary employment. I will also discuss the consequences of meaningless work for mental health, inequality, and automation. Finally, I’ll outline two possible solutions: a universal basic income (UBI) and a shortened workweek.

Introduction

I would like to talk today about work, jobs, and alienation. Let me admit straight away: I am not an expert on this subject. Rather, this is an invitation. I want to call on others to help me think more deeply about something that many of us feel but cannot always articulate. My reflections are based on a limited set of sources, some personal experiences, and a nagging intuition that something about the way we work is fundamentally wrong.

If you do not share that feeling—if you are fully satisfied in your work—then congratulations. Truly. In fact, I am one of those lucky people: I genuinely enjoy my job. But time and again, I hear colleagues—teachers and professors alike—say that they rarely get to do the actual core of their work anymore. Instead, they are drowning in paperwork, bureaucracy, and endless tasks that feel meaningless. Since I myself would like to continue in academia, I find this worth examining more closely.

Bullshit Jobs

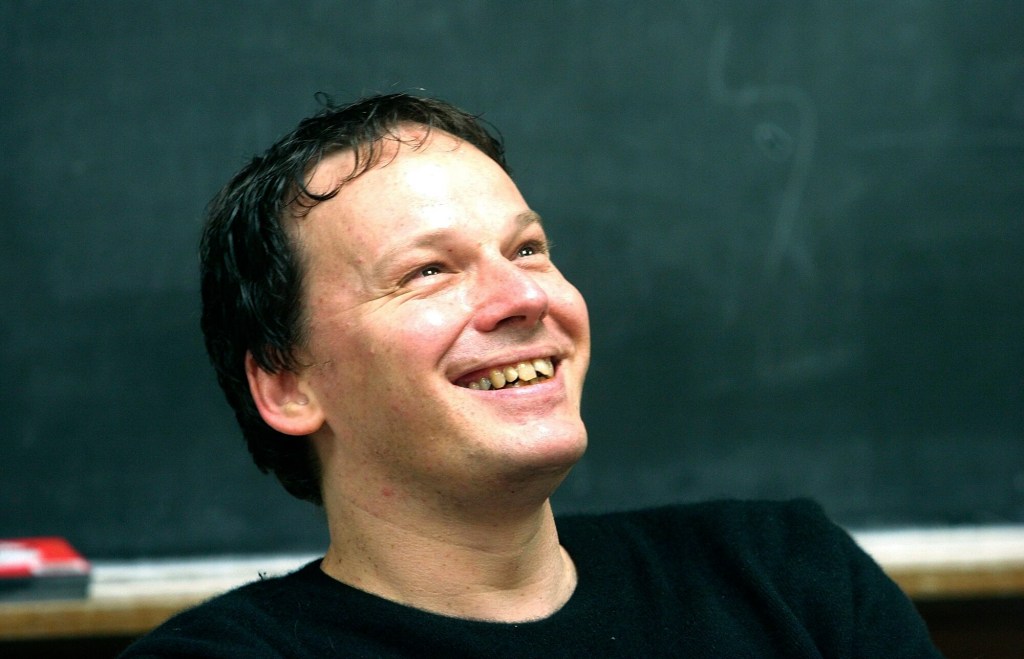

The late anthropologist David Graeber (1961–2020) became widely known for his book Bullshit Jobs (2018), alongside his co-authored The Dawn of Everything (2021). Graeber defined a “bullshit job” as:

“a form of paid employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence—even though, as part of the conditions of employment, the employee feels obliged to pretend that this is not the case” (Graeber, 2018, p. 9–10).

The crucial element here is pretending. In a bullshit job, the worker knows their tasks are useless but is forced to act as if they are essential. This leads to elaborate forms of “busywork”—inventing tasks, sending unnecessary emails, generating reports no one reads—simply to give the appearance of productivity. Energy is not just wasted, it is misdirected into sustaining the illusion.

Graeber drew inspiration from philosopher Harry Frankfurt’s concept of bullshit as something distinct from both truth and lying. Bullshit is speech without concern for truth, and similarly, a bullshit job is work without concern for real value.

Surveys suggest that around 40% of people consider their jobs meaningless.1 And even when people don’t see their entire job as pointless, many feel that significant portions of their daily tasks are unnecessary.

Take the example of a teacher. Increasingly, teachers are required to document every interaction with a student in systems like Smartschool. A minor incident must be logged, checked by a school counselor, written up as a report, double-checked by an administrator, and then archived—usually never to be looked at again.

Instead of freeing teachers to spend more time with students, this administrative load often increases pressure. In some schools, this has led to open conflict between teachers and administrative staff. Teachers complain that paperwork steals time from preparing lessons, grading, and actually talking with students—the real purpose of teaching.

For Graeber, this isn’t just about inefficiency. It is an ethical problem. Bullshit jobs deny people recognition as human beings. They strip work of dignity. He argued that the rise of such jobs is tied to the bureaucratization of institutions, a process rooted in a lack of trust. Once organizations grow large, they create layers of monitoring, checking, and verifying. Out of this distrust, bullshit proliferates.

Alienation in Marx

The young Karl Marx explored alienation in his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844—a set of writings often called the Paris Manuscripts, composed before The Communist Manifesto. These early texts reveal a surprisingly humanistic side of Marx.

Marx’s central idea: capitalism is destructive because it alienates human beings. While later Marx emphasized economic structures and scientific analysis, his early critique was profoundly ethical.

Alienation was not Marx’s invention. The concept can be traced back to Hegel and appears throughout the history of philosophy. In general terms, alienation means being estranged from oneself—being unable to express oneself authentically and autonomously. For Marx, the primary medium of self-expression is labor.

“For labor, life activity, productive life itself, appears to man in the first place merely as a means of satisfying a need… Yet the productive life is the life of the species. It is life-engendering life. The whole character of a species, its species-character, is contained in the character of its life activity; and free, conscious activity is man’s species-character” (Marx, 1844).

Labor, then, is not merely a way to survive. It is the activity that makes us human, just as painting makes a painter.

But under capitalism, this essence of humanity becomes distorted. Why? Because:

- The worker’s product does not belong to them. They “give birth” to the wealth of others.

- The worker’s activity is fragmented. They perform tiny, repetitive tasks and cannot see themselves as the creator of a whole.

Thus, workers are estranged not only from their products but also from their own human potential.

To me, Marx’s concept of alienation is perhaps his most compelling contribution. Unfortunately, later in life he downplayed these ethical concerns in favor of presenting himself as a scientific analyst. Still, his insights about alienation remain vital.

Yet, something is missing in Marx. He focused almost exclusively on labor, as if it were the only foundation of human meaning. I think that goes too far. Alienation also has a psychological dimension, which is where Erich Fromm comes in.

Alienation in Fromm

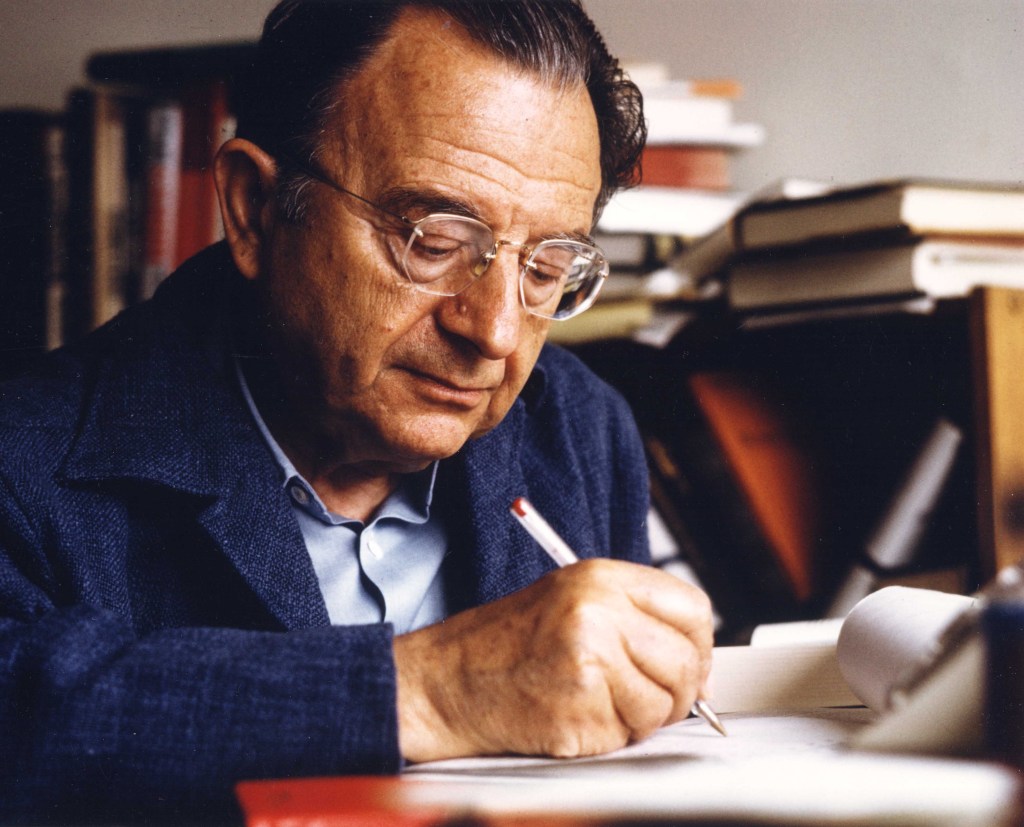

The psychoanalyst and social philosopher Erich Fromm built on Marx’s ideas but shifted the focus. For Fromm, alienation is not just about losing one’s product. It is about being forced into activities that do not align with one’s inner subjectivity.

Take the example of an IT worker who secretly longed to be an artist. He chose IT not out of authentic passion but because it was profitable and made his parents proud. Fromm would say this person lives a passive life, governed by external forces.

This is what Fromm called the alienation of “having” rather than “being.” Advertising is the clearest illustration: it convinces us we “need” things we do not really need. Under consumer capitalism, desires are manufactured and manipulated, leaving us with the sense that life is happening to us rather than being lived by us.

Alienation extends beyond the workplace into consumption. Our very wants are colonized. Today, instead of propaganda alone, it is algorithms shaping our desires: the push to buy the latest iPhone, binge the newest series, or pursue career milestones imposed by collective expectation.

Chuck Palahniuk’s novel Fight Club (1996), later adapted into the cult film, captured this perfectly:

“Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don’t need… Our great war is a spiritual war. Our great depression is our lives” (Fight Club, 1996).

Ironically, although Fight Club has been appropriated by the far right, its original message was a left-wing critique of capitalism. Fromm’s distinction between authentic being and alienated having lies at the heart of it.

Connecting this back to Graeber: a bullshit job is the fusion of Marx’s and Fromm’s alienations. Materially, the worker produces nothing of value. Psychologically, they must lie to themselves and others, pretending their job matters.

Why is Work Supposedly So Important?

Interestingly, the cultural glorification of work is a relatively recent phenomenon. Historically, to work was a mark of poverty. The wealthy prided themselves on not having to work, spending their time on philosophy, theology, or science.

What changed? The Protestant Reformation, particularly Calvinism. In The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905), sociologist Max Weber argued that Calvinists saw labor as the supreme expression of devotion to God. Work was a way to prove one’s salvation. Over time, this religious obligation turned into an economic ethic: debt and labor intertwined.

Thus, the work ethic became bound to capitalism itself. Today, idleness is considered shameful. To be unemployed or unwilling to work is condemned as laziness.

This view cuts across political lines. Even left-leaning figures like Bernie Sanders have proclaimed that work is “the most important thing in a person’s life.” I strongly disagree. Work can provide meaning, but it is not the only or highest source of meaning.

Perhaps Marx was right in seeing creative activity as central, but creative activity is not the same as a job. Painting, gaming, giving a talk—these are all forms of labor, even if unpaid.

Universal Basic Income and the Four-Day Workweek

If so much work is meaningless and alienating, what alternatives exist? Two promising proposals are:

- Universal Basic Income (UBI).

- A shorter workweek (three or four days).

Personally, I favor UBI.

UBI is not a socialist invention. It has deep roots in liberal and even capitalist thought. John Stuart Mill discussed it in Principles of Political Economy (1848). Thomas Paine, often called the father of human rights, saw it as a basic entitlement. Even Adam Smith, remembered as the father of capitalism, was a moral philosopher first. He hoped that capitalism would generate enough wealth to lift everyone out of poverty and reduce the necessity of work.

In the 20th century, support for UBI came from across the spectrum. Martin Luther King Jr. endorsed it as a tool for racial justice. Milton Friedman, champion of neoliberalism, supported a version of it to ensure participation in the market.

UBI is not just theory. Experiments have taken place in Finland, Kenya, and elsewhere. Since 1982, Alaska has implemented a form of it, paying residents annual dividends from oil revenues—ranging between $1,000 and $3,000.2 It was Andrew Yang’s main point in his 2020 presidential run for the Democratic Party.3 Even popular culture references it: in The Simpsons Movie, Homer Simpson is handed a check upon arriving in Alaska.

The real promise of UBI is empowerment. Workers gain leverage. If your boss gives you a meaningless or exploitative job, you can afford to walk away.

Alongside UBI, the four-day workweek offers another path. More free time means shifting our cultural Zeitgeist: normalizing life beyond work, encouraging social connection, and reducing burnout. Those who love working can still do so. But people who prefer to “live rather than labor” should not be stigmatized.

Conclusion

So, why don’t we like our jobs? Because many of them are bullshit. They alienate us—materially, as Marx described, and psychologically, as Fromm warned. They exhaust us, distort our desires, and leave us feeling trapped.

But work does not have to be this way. It is not inherently noble, nor inherently degrading. It is one possible source of meaning among many.

A future with UBI and shorter workweeks could allow us to reclaim labor as authentic creativity rather than forced survival. Perhaps then, we might finally live as free human beings—not as workers, but as creators.

- https://www.meerwaardeinwerk.nl/een-bullshitbaan-of-zinvol-werk/ ↩︎

- https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/alaska-is-a-case-study-for-universal-basic-income/ ↩︎

- See his book The Way on Normal People. I quite like it and it was my first introduction into UBI ↩︎

Leave a comment